A presentation I did, posted on my travel blog.

2015 in Books

This is the first year I have used Goodreads to track what I read. My books of 2015 are now listed on this report. My total was a slightly disappointing 50 titles, though it’s possible I missed a few early in the year, and I started probably another 30 or 40 that I have not yet finished. Still, I like to reflect on what I have read, and I thought I’d give here the list with brief reviews. If I posted a review of a particular work on Goodreads, I link to it in the title.

My order, within each category, is subjective and intuitive, rated roughly by significance to me. Continue reading

O Emmanuel: Meditations on the O Antiphons

Last year I wrote a series of posts on the O Antiphons, intending to do one per day until Christmas. I got through four and posted a belated O Oriens and O Rex Gentium, but the seventh, O Emmanuel, I never completed. This year, living in Eastern Europe, I’ve not been getting the usual sights and sounds of the Christmas season. Stripping away the family and commercial jollity gives a different feel to these last weeks of December, and I doubt the Georgian festivities surrounding Eastern Christmas (January 7) will wholly replace it. But it is still a good time to meditate on these traditional Latin hymns, as midwinter brings in the new year.

* * *

The seventh O Antiphon is to Emmanuel (God with us).

The seventh O Antiphon is to Emmanuel (God with us).

O Emmanuel, rex et legifer noster,

exspectatio gentium, et salvator earum:

veni ad salvandum nos,

Domine, Deus noster.

O God with us, our king and lawgiver,

the nations’ expectation, and their savior:

come to save us,

Lord, our God.

We conclude Advent with an antiphon to Christ Emmanuel, whose sign embodies the focal truth of the incarnation: that God is with us.

There seems little to say about this antiphon. It is brief and direct, summing up the ones that came before. We may note a slight shift from the previous verse: Christ is now not merely the nations’ desire, but their expectation. Christ is in the Virgin’s swelling womb; in the fullness of time, he will appear. Still there is a double significance; we sing the antiphon in light of the parousia (coming) for which we wait, as Christ’s Body is built up on earth and eagerly looks forward to its birth under a new sun.

But we should not miss the beautiful simplicity of this antiphon, which proclaims Christ as “our king and lawgiver,” our savior, and most importantly, Emmanuel.

Baptized Imagination: A Short Review

“It is God who gives thee thy mirror of imagination, and if thou keep it clean, it will give thee back no shadow but of the truth.” (George MacDonald, Salted With Fire)

George MacDonald’s theological vision was vivid, deep-rooted, and influential for later Christian luminaries such as G. K. Chesterton and C. S. Lewis. Yet he eschewed excessively abstract theologizing and generally expressed his beliefs in an unsystematic and image-rich fashion. In this book, Kerry Dearborn attempts to piece together his thought from the range of his writings. Baptized Imagination: The Theology of George MacDonald is worth reading just for the joy of so many wonderful quotes, though as an overview of his thought and influences it will be most of interest to theologians and literary critics.

George MacDonald’s theological vision was vivid, deep-rooted, and influential for later Christian luminaries such as G. K. Chesterton and C. S. Lewis. Yet he eschewed excessively abstract theologizing and generally expressed his beliefs in an unsystematic and image-rich fashion. In this book, Kerry Dearborn attempts to piece together his thought from the range of his writings. Baptized Imagination: The Theology of George MacDonald is worth reading just for the joy of so many wonderful quotes, though as an overview of his thought and influences it will be most of interest to theologians and literary critics.

The key to MacDonald’s whole theology is his belief in the infinite yet intimate love of God, which is nearer to us than we are to ourselves. This Trinitarian love bursts all systems that seek to confine it; it washes away fear and nurtures all created life. It is the source of all genuine knowledge, which is realized through encounter and subsequent obedience. MacDonald frequently portrayed God through familial imagery, using warm paternal and maternal figures in his fiction. This love of a divine “motherly Father” lay at the center of all his writing.

Dearborn argues that to MacDonald as author and theologian, the most significant human faculty was the “baptized imagination.” This is not to be conflated with fancy. Fancy rides upon idle emotions, and the result is often illusion, distortion, and a facile approach to life. But imagination is an attribute of the creator God, part of the self-giving love that upholds reality. Human imagination, cleansed by holy rebirth and enlivened by this same love, is constrained by love and so remains always in the light of the truth. Imagination is what enables the mind to overcome the dualities imposed by the intellect and discover new depths. Thus the imagination stands above knowledge and as partner to the intellect in the discovery of truth. We have here the beginnings of a theological aesthetics.

But the implications of this go beyond how we make art; as Dearborn argues, MacDonald also understood that this problematized any theology that rendered God too abstract, remote, and theoretical. The Bible is not to be read as a scientific text, but as witness to a singular concrete truth, Christ, who is grasped by the intellect only through the heart. Any theology which claims comprehensiveness is thereby demonstrated to be false, for no system can contain the eternal. This explains the impressionistic and occasionally inconsistent quality of MacDonald’s speculations, for they arose chiefly from the richness of his spiritual life.

However, it is clear from this study that MacDonald was not, as some have regarded him, a liberal, nor, unless one accepts the severe standards of nineteenth century Scottish Calvinism, a heretic. His relationship with the Federal Calvinism of his youth was certainly troubled; but he was not a “lone mystic.” His ideas about God and scripture were developed in dialogue with a circle of devout clergymen that included F. D. Maurice and A. J. Scott. Many of these men (like MacDonald himself) had been sacked from churches and colleges for their espousal of unlimited atonement, or doubting that Hell is neverending, but they were avid readers of the Church Fathers and found support for their beliefs in classical Christian teaching. Particular British and German Romantics such as Coleridge, Wordsworth, and Novalis were also among his heroes, though he rejected much of the Romantic movement for its pursuit of ephemeral feeling.

Because MacDonald constantly labored to emphasize the limitless love of God, and because his own life was so full of tragedy and hurt, he was often forced to ponder the question of suffering. He believed sufferings, though they arise from evil, can work to purify and redeem; they are inadvertently appointed ministers of the divine Healer, who submits to their pain alongside us. MacDonald described old age as a blessed return to the vulnerability of childhood, a preparation for rebirth.

A striking pseudo-Platonic image used by MacDonald depicts God as the sun, and evil as shadow. The consuming fire of God’s love makes things pure and transparent as glass, and the shadows vanish. This painful process is one of un-making, but it is also one of union and recreation. It is the struggle that defines mortal life, and its end is the perfect victory of Love. “Love,” MacDonald taught, “has a lasting quarrel with time and space: the lower love fears them, while the higher defies them.” MacDonald’s infamous universalism (“death alone can die everlastingly”) was not grounded in his affirmation of a particular theo-logic, but his simple conviction that the profound and unceasing love of God would not give up on sinners even in Hell.

Dearborn occasionally attempts to put MacDonald in dialogue with later and better-known theologians such as Barth, though this rarely amounts to more than scattered comparisons. She openly confesses that she regards MacDonald as “prophetic” for contemporary theological concerns. But this book, fortunately, does not read either like an academic dissection or a hagiography. It is a sound and illuminating discussion of MacDonald’s ideals, and I highly recommend it.

Religion and Fundamentalism in the Sunshine

The other week I watched the 2006 science fiction film Sunshine, a box office flop that got moderately positive reviews from critics, with some considering it a masterpiece. It tells of a small crew on a desperate mission to reignite a dying sun and save humanity. There is much to admire about the film’s visual design, acting, and storytelling elements. Like many critics, I did grow increasingly unenthused with the horror-suspense sequence the story morphed into in the last act, but nevertheless my overall experience was positive.

The shift in tone at the climax is effected when an antagonist crashes into the scene, the disfigured and crazed Captain Pinbacker. After deliberately sabotaging his own mission, he was abandoned to himself on Mercury for years. Now he wanders around the protagonists’ ship, murdering its crew, and explains his motives along these lines: the sun, the source of all human existence, is dying. While alone in the cold insensibility of space, he had a religious experience and realized that human existence is so insubstantial, it ought not to interfere with what God wills–it must allow the sun, and humanity, to die, and so find Heaven. Conceptually interesting, the character is little more than a ranting monster on screen. That said, the character plays a role invested with deep thematic significance, for he is intended as a pointed allegory for religious fundamentalism.

The Assyrian Fathers of Kakheti

From my travel website, some interesting (to me) church history.

The Wound and the Blessing

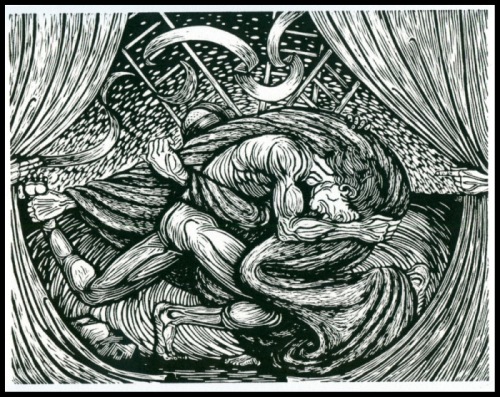

When I began writing this meditation on Jacob wrestling with God and its implications for the spiritual life, I did not intend it to be another essay on suffering. Yet the theme came of its own accord, and has some continuity with thoughts posted here, here, and here.

The story, found in Genesis 32, should be familiar. Jacob, traveling to meet his estranged brother Esau, camps alone at the ford of Jabbok.

And Jacob was left alone; and a man wrestled with him until the breaking of the day. When the man saw that he did not prevail against Jacob, he touched the hollow of his thigh; and Jacob’s thigh was put out of joint as he wrestled with him. Then he said, “Let me go, for the day is breaking.” But Jacob said, “I will not let you go, unless you bless me.” And he said to him, “What is your name?” And he said, “Jacob.” Then he said, “Your name shall no more be called Jacob, but Israel, for you have striven with God and with men, and have prevailed.” Then Jacob asked him, “Tell me, I pray, your name.” But he said, “Why is it that you ask my name?” And there he blessed him. So Jacob called the name of the place Peniel, saying, “For I have seen God face to face, and yet my life is preserved.” The sun rose upon him as he passed Penuel, limping because of his thigh.

The stranger is usually seen in the Christian tradition as Christ himself. Perhaps the most conventional moral interpretation emphasizes Jacob’s persistence. In refusing to let God go, he receives a blessing; so also must we be persistent in prayer and struggle in faith. Another, almost opposite interpretation sees the struggle as God destroying our willfulness, teaching us to submit and “let God.” But these readings in themselves make little sense of the most striking aspects of the text.

My own exegesis of this passage focuses on the wound, which I first began to contemplate after reading a passage in Scott Cairns’s memoir Short Trip to the Edge. Here, an ordinary Athonite monk uses the story of Jacob and the stranger to illustrate for Cairns a mystery of the life of prayer.

[Father Iakovos] placed a hand on his chest, just above his abdomen. “You have to hold on to Him,” he said, “with all your strength…. You have to plead with Him to meet you here…. And when He arrives, you must hold on to Him and not let go. Like Jacob,” he said, “you must hold on to Him…. And like Jacob,” he met my eyes with new intensity, “you will be wounded. Like Jacob, you must say, ‘I will not let You go unless you bless me,’ and then the wound, the tender hip thereafter, the blessing…. He is everything,” Father Iakovos continued, “and ever-present. He is never not here,” he said, touching his upper abdomen, “but when you plead to know He’s here, and when He answers you, and helps you to meet Him here, you will be wounded by that meeting. The wound will help you know, and that is the blessing.” (136-137)

Dominus Historiae: Conclusion

The younger Daniélou

Continuing my review of Jean Daniélou’s The Lord of History from here.

Before I get into the meat of this conclusion, comparing Daniélou’s views of history to those of other recent Christian thinkers, I would like to contrast him with someone whose views were opposite in just about every respect: his brother.

The spiritual trajectory of Jean Daniélou’s younger brother, Alain, was a great influence on Jean. The Daniélou family was, to put it mildly, religiously conflicted. Whereas Jean took the faith of his devout mother (while rejecting her harsh moral vision—she was considered a fanatic even among Catholics), Alain was closer to his radically anticlerical father, and in his teens repudiated Christianity altogether. Jean joined the Jesuit order at the age of twenty-four, with numerous academic honors behind and before him, but Alain was more interested in the arts, especially dance, photography, and music.

Alain was a homosexual, and identified as such from a young age. His first sexual experiences at university also marked a religious awakening; thereafter, he regarded his sexuality and spirituality as inextricable. Accompanied by a gay lover, Alain studied music and philosophy in India and eventually converted to Shaivite Hinduism. He believed that Shaivism represented a primitive, erotic, Dionysian spirituality that organized religions have by and large destroyed. He wrote prolifically, both as a polemical opponent of monotheism and a scholar of Indian history and religion.

Despite their deep differences, the famous brothers remained affectionate throughout their lives. They were, indeed, very different; Alain characterized Jean as “nervous, frail, and agitated,” whereas he regarded himself as “virile,” adventurous, and supremely confident. Alain further believed that the Catholic Church to which Jean was devoted had viciously suppressed the pure, original faith of Jesus; he seems to have regarded Catholicism as the most antihuman and masochistic institution on earth, despite his respect for certain Catholic mystics, not to mention his own brother, a cardinal.

When Jean died in a house of ill repute and the press was full of the scandal, Alain wrote a defense of his older brother, insisting that Jean’s character was saintly and humble and incapable of hypocrisy, and that Jean’s life was dedicated to the service of social outcasts (though Alain could not resist adding that he would have been very happy had his brother experienced the joys of sex before his death). Alain Daniélou continued to publish until his death in 1994 and remains esteemed in his field.

As fascinating as it would be to produce an extended comparison between the works of these brothers, I must restrict myself (partly through lack of adequate reading) to the themes raised by Jean in The Lord of History. First, however, it would be best to offer a more complete description of Alain’s position.

The Gospel of the Princess Kaguya

“The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter,” one of Japan’s oldest folk stories, has long been a favorite of mine. Last night, I watched an adaptation by Studio Ghibli, The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013), which I heartily recommend. The animation was hand-drawn over eight years, and it may be the last film ever directed by now-octogenarian and acclaimed Studio Ghibli co-founder Isao Takahata. In addition to the quality of the animation and storytelling, the myth itself is full of the “glorious sadness” of paganism, the mixture of beauty and fatalism that flavors all the best stories of the pre-Christian world.

“The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter,” one of Japan’s oldest folk stories, has long been a favorite of mine. Last night, I watched an adaptation by Studio Ghibli, The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013), which I heartily recommend. The animation was hand-drawn over eight years, and it may be the last film ever directed by now-octogenarian and acclaimed Studio Ghibli co-founder Isao Takahata. In addition to the quality of the animation and storytelling, the myth itself is full of the “glorious sadness” of paganism, the mixture of beauty and fatalism that flavors all the best stories of the pre-Christian world.

Here is the story, in brief summary. A poor bamboo cutter finds a tiny, luminous baby girl in a bamboo grove. He raises her, and she grows supernaturally quickly into a young woman. Meanwhile, the bamboo cutter receives gifts of gold in the bamboo he cuts and is soon very wealthy. He purchases a magnificent house, and his foster-daughter, Princess Kaguya, is renowned for her beauty and grace. She acquires many suitors, but sets them on impossible tasks. Even the Emperor takes an interest in her, and she rebuffs him. In time, she reveals that she comes from the moon, and she must return to her people imminently. Despite the efforts of her foster family and the Emperor himself, the semi-divine moon people come and carry her back off to heaven.

The original narrative has a further subplot involving the Emperor which does not make it into the movie (the reason for which will become clear later in this review). After Kaguya refuses to marry the Emperor, they become correspondents and friends. When the moon-people fetch her, they give her a drink from the Elixir of Life. She is not allowed to give this to her elderly father, but she can and does send a phial to the Emperor. The Emperor, in mourning at having lost her forever, burns the elixir on Mount Fuji.

As I have lately been studying principles of Christian response to nature-myth (e.g., here), I wish to discuss The Tale of the Princess Kaguya as a truth-telling story that points to fulfillment in Christ. By this I do not mean that there is a Christian message coded into the film, or that we can turn the story into a Christian morality tale; but I do mean that its truthfulness about reality necessarily results in a hidden meaning that may be illuminated by the work of Christ.

Dominus Historiae: Part III

Continuing my review of Jean Daniélou’s The Lord of History from here.

Daniélou has by this point given us a fairly extensive theology of history. What is left for him to discuss but the implications of this theology for ordinary life? What values are promoted by this theology? Daniélou’s exegetical focus is even more intense here than the last part. The apostle Paul serves throughout as an example of these virtues in action, and his epistles are heavily quoted.

After completing this summary here, in the next and final entry, I will conclude with some meditations on Daniélou’s theology of history as a whole, and compare his views with those of some other thinkers I’ve read recently. Continue reading